10 things you need to know about neglected tropical diseases in 2025

Over one billion people are affected by neglected tropical diseases (NTDs), yet despite this vast figure, they continue to be overlooked. The majority live in the most remote areas of the world’s lowest income countries.

The diseases can be distressing, disfiguring and stigmatizing. Many are excruciatingly painful, and they are often deadly. However, they can be treated – and they can also be prevented. World NTD Day was designed to put a spotlight on them and to remind the governments of affected countries, pharmaceutical companies, philanthropists and the governments of higher-income nations – all of whom have the power to support – that there is much more to do.

This World NTD Day, we’re taking stock of the progress made to prevent, control, eliminate and eradicate NTDs, as well as highlighting the huge challenges that remain. Below is an overview of the current state of play: five notable achievements, and five of the biggest obstacles that remain and continue to block progress in the fight against NTDs.

5 notable achievements

1. Noma, a disease that is especially deadly for children, was added to the list of NTDs in 2023

The fact that the exact causes of noma remain a mystery indicates just how neglected the disease is. It was finally added to the World Health Organization’s official list of NTDs in 2023, and this higher visibility could be a gamechanger.

Due to limited research, difficulties reaching people affected and the fact that many are hidden away due to stigma, it is unknown how many people are impacted by the disease. Current estimates are more than 25 years old – those indicate 140,000 new cases occur each year, while 770,000 people are living with its lasting effects. The word noma comes from the Greek word “to devour,” because that is what it does to the skin. It starts in the mouth where ulcers quickly develop and turn gangrenous, eating away at the tissue. It is easily treatable with antibiotics if caught early, but when gangrene sets in, it is fatal for 90 per cent of children. Survivors are left with severe facial disfigurement and often physical disabilities, such as difficulties speaking and eating due to the destruction the disease causes inside the mouth. The disfigurements are so highly stigmatized that families hide those affected away from society.

The campaign to add noma to the list of NTDs was led by Nigeria and backed by Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF), among others. We have supported Nigeria’s Ministry of Health with a noma hospital in Sokoto for over a decade, providing treatment, reconstructive surgery, mental health support and community outreach services. Now that this deadly disease has been added to the list of NTDs, it is hoped there will be more investment into understanding, preventing and treating it.

2. The END Fund filled the gaping hole left by the UK, after it brutally cut its support to NTDs in 2021

When the UK slashed its overseas aid budget in 2021, the crucial role it played in purchasing life-saving medicines to treat visceral leishmaniasis – also known as kala-azar – in East Africa ended almost overnight. Historically one of the largest funders of NTDs, and of visceral leishmaniasis in particular, the UK’s brutal withdrawal of funding left a gaping hole in the fight against these diseases.

The parasite is transmitted by sandflies. It progressively attacks and destroys tissue that is vital for immune function and without treatment can rapidly become fatal. Initial mild symptoms develop into a prolonged fever, enlarged spleen, anemia and substantial weight loss. The cure is a combination of two drugs injected daily for 17 days. With the UK funding cuts, access to this treatment was in jeopardy. However, through intensive advocacy by MSF and others, a new funder – the END Fund – was found. Nevertheless, access to prompt diagnosis and treatment remain huge challenges for many visceral leishmaniasis patients around the world – especially in East Africa. Recent global political shifts, as well as many competing emergencies, are threatening funding more than ever. Sustainable, longer-term support is required to ensure we make progress to prevent, cure and eventually eliminate visceral leishmaniasis and other NTDs.

3. MSF will soon join the fight against another NTD: female genital schistosomiasis

Jonglei State in South Sudan, where MSF runs a hospital in the remote town of Old Fangak, has the highest documented burden of schistosomiasis in the country. Here we suspect many girls and women suffer from an advanced form of the disease known as female genital schistosomiasis (FGS). We are currently looking at ways to better identify and address the burden of the disease in humanitarian contexts, not only in South Sudan but also in other MSF projects in countries where the parasite is also present.

Schistosomiasis is caused by a parasite that resides in snails in freshwater lakes and rivers. People become infected through contact with infested water. Although schistosomiasis is one of the “big five” that receive most of the limited funding that is available for NTDs – the others being elephantiasis, trachoma, river blindness, and intestinal worms – the interventions that exist to address it are largely preventative. This means that girls and women who are already suffering with advanced disease as a consequence of heavy infections and who need treatment are forgotten about.

Patients with FGS have a high parasite load within their reproductive and urinary system, causing debilitating inflammation, and even sometimes progression to fatal cancers. It is a highly neglected form of an already neglected disease. Our focus will be on ensuring women and girls are accurately diagnosed and provided with the best possible treatment.

4. In 2024, Gavi launched an ambitious program to improve vital access for patients to the rabies vaccine after animal bites

Except for dengue fever and chikungunya, rabies is the only vaccine-preventable NTD. However, in many of the 150 countries where it is still a huge threat to human life, stocks are extremely limited and the cost of the vaccine is high.

Rabies is transmitted to humans through bites from infected mammals, most commonly dogs. If post-bite medical care is sought swiftly, it can be prevented. However, if the post-exposure vaccination is not received in time, the patient becomes infected with the virus. When clinical symptoms develop, it’s already too late – the disease is 100 per cent fatal because there is no cure.

In wealthy countries with easy access to vaccines, dogs are among those vaccinated to keep the disease under control. While this move from Gavi, an organization focused on increasing equitable and sustainable use of vaccines, will not include any vaccinations for dogs, countries can include rabies on the list of vaccines they request from Gavi for humans who are bitten. This means that ministries of health will finally be able to stock the vaccine in clinics and hospitals and be able to quickly vaccinate any people bitten by dogs at no cost to patients.

5. Sleeping sickness has been eliminated in many countries, Guinea being the latest on the list

Over the past 25 years, there has been a 97 per cent reduction in the number of people suffering from sleeping sickness, leading to its elimination as a public health problem in Equatorial Guinea, Ivory Coast, Benin, Togo, Uganda, Chad in 2024 – and, now, Guinea. This achievement is testament to what can happen when there is political will, funding, and also if pharmaceutical companies invest in NTDs and develop safer, more effective treatments.

However, 1.5 million people are still at-risk of the disease.

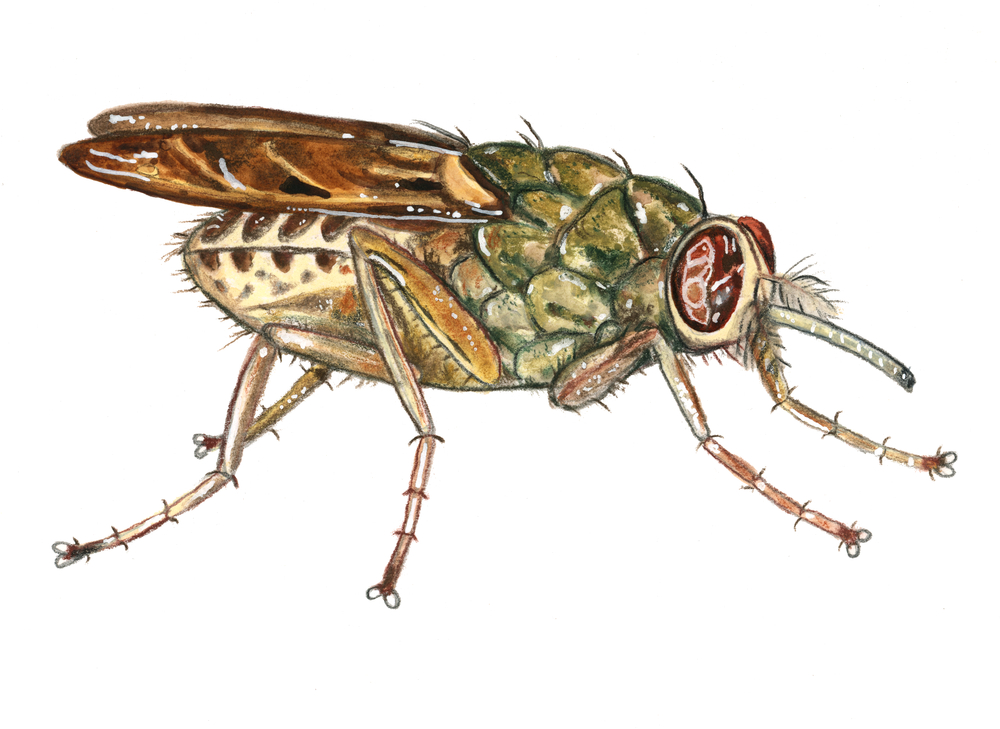

Sleeping sickness is caused by parasites transmitted from tsetse fly bites. In one form of the disease it can move to the acute stage when the parasites attack the brain and spinal cord withina matter of weeks. This causes sleep disruption, convulsions, confusion and eventually a coma. Without treatment, it is fatal.

For many decades, the only cure was an arsenic derivative that killed one in 20 patients. In the 1970s, a new drug revolutionized the odds of survival. However, in the 1990s, the manufacturer, Sanofi-Aventis, wanted to discontinue production, which would have been a major step backwards. Fortunately, pressure from the WHO and MSF persuaded Sanofi-Aventis to prioritize sleeping sickness, donate the drug and develop new, better, more patient-friendly treatments in collaboration with DNDi, the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative. This collaboration and continued investment have led to further advancements in medicine. Now, a simple and safe oral treatment is available.

5 biggest obstacles

1. New conflicts are putting in jeopardy much of the progress made in the fight against NTDs

When war breaks out, neglected tropical diseases become even more neglected. Already weak health systems further collapse, surveillance is disrupted, and even diseases once controlled can reemerge with a vengeance. Vigilance is therefore vital.

In North Darfur, Sudan, we are on high alert. Although there have been no confirmed cases in our emergency response projects there yet, other regions in Sudan are known hotspots for visceral leishmaniasis. We know from our long history in the country the conditions of displacement and malnutrition are rife for an explosive outbreak of the disease, so we are preparing our teams for the possibility of cases. When huge numbers of people with no previous exposure to the disease, and therefore no immunity, are displaced to areas where it is endemic, it can put them at huge risk. Additionally, when patients with the disease have to flee and end up in areas where the disease is not present, they can transmit it to vulnerable people living there. This is our fear for people in North Darfur and many other parts of Sudan where mass displacement and the destruction of healthcare services are occurring.

Access constraints have been a hallmark of the conflict in Sudan, with supply trucks containing life-saving medicines being held up for months, so we are pre-positioning stocks. Diagnosing the disease is complex: medical teams need the tools to diagnose cases earl, and rapid testing will only be positive in some cases – in some other cases it requires skilled staff to take tissue samples from internal organs. It also requires hospitals with functioning labs to run tests on blood and tissue samples. In North Darfur all of those things are in short supply. Additionally, health teams are less familiar with the disease because historically North Darfur has not been a hotspot area, compared to other parts of Sudan such as Gedaref state, where the majority of cases tend to occur.

With this backdrop as the context, we’ve sent rapid tests and drugs to North Darfur, and we’ve trained our teams so if an outbreak occurs we can support the Ministry of Health to respond quickly.

2. Major financing gaps persist

NTDs face huge funding issues, but the “big five” get the majority of what little is available: they can be more rapidly addressed by delivering blanket drug distributions to large numbers of people at once and are therefore popular with donors.

For the other close to 20 NTDs, methods available for controlling the diseases can be more complicated or expensive, and funding is much more limited. The WHO has estimated two billion dollars was missing to control NTDs from 2023 to 2025 alone, excluding the cost of the medicines.

International donors like France, the UK, the EU and BRICS could make a significant impact, but have worryingly been reducing their funding, rather than increasing or at least maintaining their commitments to these diseases of poverty. (BRICS countries include: Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa, Egypt, Ethiopia, Indonesia, Iran and the United Arab Emirates).

3. Snakebites remain the biggest killer of all NTDs, but treatments are in short supply, exorbitantly priced and many antivenom products are substandard

Most snakebite victims still have no access to antivenoms because they live too far from a health facility that could potentially have the antidote in stock. Even if they could reach a clinic, they would be unable to afford the high cost of the product.

Antivenoms are tailored biological products intended for use in specific regions so they are produced in small quantities. Their potency is often not as strong as it should be, so victims need to purchase many vials. Regulation of the market is very limited. It is up to each country where antivenom is used to assess the efficacy of the product against the venoms of the local snakes. Even testing basic, regular medicines is difficult when the health system is weak, so in practice many countries cannot conduct antivenom assessments.

The good news is that in 2017, the WHO launched an assessment of existing products, requesting samples from various manufacturers, and the results are being disclosed in real time. We hope this audit will put pressure on the producers to improve their products. In addition, we hope it will trigger more domestic and international financing to acquire more doses of quality antivenoms and distribute them free of charge to snakebite victims in need.

4. Diagnostic tests are vital, but they are in short supply

Continued surveillance of NTDs is vital for keeping them under control and diagnostics are key. Many diagnostic tests are not always accurate, so investment is needed to improve them. Although some new diagnostics are being developed, they are for very niche markets, so it is difficult to persuade large companies to invest in them. There is far less financial backing for diagnostic tests for NTDs. Many NTD medicines are produced by large drug companies like GSK who may wish to donate the drugs in exchange for a good reputation. The companies producing diagnostic tests are much smaller by comparison and this is not an option for them. There is no global access mechanism for diagnostic tests for NTDs, so countries have to individually purchase their own.

It is vital diagnostics are also brought closer to communities. The ability to effectively diagnose these diseases early and to initiate prompt treatment is essential for patients’ wellbeing and to prevent the spread of disease. This requires reliable, affordable, easy to use rapid tests.

5. Reduced funding for research into NTDs is putting major medical breakthroughs at-risk

In the last few years, after relative stability, funding for research and development for NTDs notably declined. If this continues as a downward trend, the final steps of major medical breakthroughs will be put at risk. Research is time and resource consuming: many early innovations never make the cut in terms of efficacy and safety, and so have to be abandoned. Late-stage trials are expensive. If there is no funding for them, new compounds to treat NTDs will have no chance of coming to market to save lives.

Visceral leishmaniasis, dengue and Chagas disease, for example, have new compounds ready for clinical trials, and a vaccine for schistosomiasis is also in the early stages of development. Snakebites are another NTD where clinical trials could soon start. In 2019, the Wellcome Trust invested in a seven-year research and development project for snakebites, but this funding is expected to come to an end in 2026. Although there are some exciting new products in the pipeline – with a universal antidote being the desire of most within the research community – in order for this to happen, longer-term funding needs to be prioritized and sustained. The future of all of this progress is now hanging in the balance.