48 hours at the U.S.-Mexico border

Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) project coordinator Belen Ramirez recounts two days of work alongside volunteers from Arizona-based Samaritans, providing aid to people crossing the border into the unforgiving Sonora desert.

It’s early morning in Arizona, just before daybreak, and I am driving on an unpaved road along the border wall between the United States and Mexico. It is raining and I can hear thunder in the distance.

Driving just ahead of me are volunteers from Samaritans who for decades have provided water, food and other essential items to migrants who cross the border into southern Arizona. We’re on our way to the End of the Wall, a volunteer-run makeshift camp located near a gap in the wall that runs along the southern United States border with Mexico.

This remote part of the Sonora desert, where the over nine-metre steel bollard wall ends and a chest-high fence continues to mark the border, is a crossing point for people entering the U.S. from Mexico in hopes of claiming asylum. For the past five weeks as a project coordinator with MSF, I have been supporting Arizona-based volunteer groups like the Samaritans who are providing humanitarian support to migrants and asylum seekers in Arizona, including in the area where the End of the Wall camp is located.

No typical day

There is no typical day for those who volunteer at the End of the Wall camp. On some days, volunteers spend just a few minutes with asylum seekers. On other days, they can spend hours with them before U.S. Border Patrol takes them away to their Forward Operation Base in Sasabe, and later to a detention centre in Tucson where people can start the legal process for asylum. During this time, volunteers try to make people feel welcome and provide water, food, much-needed psychological first aid and information about what comes next.

This morning we are the first to arrive at the camp. Volunteers get to work and start replenishing storage bins and a cooler with snacks, and water bottles, among them 77-year-old Judy Storey, who has been volunteering with Samaritans for seven years. “When it gets really hot, we soak bandanas in ice water and bring them out,” she tells me. “People put it on their heads or around their necks, and it’s been a godsend when it’s in the 90s out here, and they have to wait five hours for Border Patrol.”

Soon, a group of men and women who have just crossed the border walk in. “Hi, welcome,” we say, “where are you from?” Some respond that they are from Cameroon. “Northwest, Bamenda,” someone says.

Another man says, “We are from Sudan, from Darfur.” He shares he fled Sudan to neighbouring Chad because of the war that started in April 2023. He then travelled for two months, starting in Morocco and then going to Spain, Colombia, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Mexico, and finally to the U.S.. “I am now on the safe side,” he says.

Outside the tent, other volunteers speak with a group of men and women from Mexico. A few minutes later, around 8 a.m., Border Patrol agents arrive to pick them up.

Asylum seekers from around the world cross at the End of the Wall camp and other gaps at the border wall in this remote region. They are dropped by guides on the Mexico side of the border and told they can surrender to Border Patrol to apply for asylum protection in the U.S. But the nearest Border Patrol station is miles away and asylum seekers must walk for hours through extreme terrain and weather conditions or wait to be picked up by Border Patrol agents.

Volunteers hand the new arrivals water bottles and snacks for the road. We tell them they are safe and try to explain what will happen next.

I notice that the man from Sudan is shaking. He asks where he is. I tell him he is in Arizona. I make sure he is able to drink water properly before a Border Patrol agent directs him to get in the car. I can only imagine what he went through to make it to this point.

The End of the Wall

Volunteers from Samaritans, No More Deaths, and Humane Borders cover morning, midday, and night shifts, seven days a week at End of the Wall camp. They often stay until Border Patrol picks everyone up around 8 a.m., 2 p.m., and 8 p.m.

There are three tents that provide shade and some protection from the elements; water bottles and tanks that are periodically replenished with drinking water; snacks and diapers in plastic bins. There is also a solar powered internet service that helps migrants and volunteers stay connected with family and emergency services, and porta potties.

Despite language barriers, and with occasional help from an asylum seeker who speaks English or an online translation app, volunteers provide some guidance about what to do next, what to expect when Border Patrol arrives, and inform them about their right to seek asylum.

Unaccompanied minors

Often volunteers see unaccompanied minors arriving at the camp. Just the day before, on a very hot summer day, Abdul*, a 17-year-old boy from Bangladesh, crossed into the U.S. at the End of the Wall camp. He looked tired and said he needed to drink water. He said he was hungry and hot.

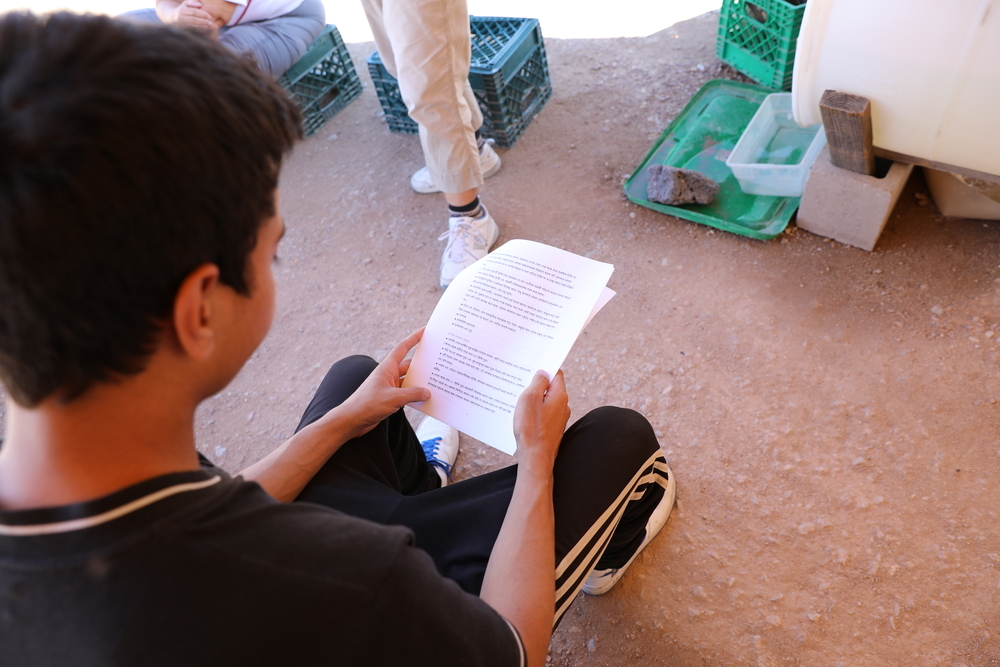

Volunteers from Samarians invited Abdul to come into a tent for shade, water, apples, and other snacks to eat. Sally Meisenhelder, a 77-year-old volunteer with Samaritans, handed him some documents in Bengali about what to expect in the next few hours and after Border Patrol picks him up. These documents have been translated recently to breach the language gap and provide some basic information to people arriving from Bangladesh.

That day, I decided to wait for a few hours with Abdul to make sure he felt safe and was not alone for such a long time, waiting for Border Patrol.

Through our language barrier, he explained that he flew from Bangladesh to Qatar, then to Paraguay or Uruguay; he was not sure which one. He then flew to Colombia and made his way north to cross the notoriously dangerous Darién Gap into Panama and continued onward through Central America and Mexico.

Most of his belongings were stolen in Mexico, he said, including his phone and passport. The only document he carried with him was a piece of paper — his birth certificate.

Another day that week, there was a group of 11 unaccompanied minors from Mexico and Guatemala at the End of the Wall camp. The youngest one was five years old. Some of the older children, aged 11 and 12 told us that they found him alone and crying when they reached the camp at dawn. They asked him to sit with them and comforted him.

The boy, Mateo, was clutching a small plastic bag attached to the rosary around his neck. Inside was a piece of paper with his mother’s phone number written on it. She was in the U.S. waiting for him.

When I met him, he kept telling me this paper was for the police. He seemed very worried about it.

I was able to call Mateo’s mother on video.

“Mommy, mommy,” he said, so happy to see her. Mateo’s mom told him to be brave and not to cry. I explained to both of them that Border Patrol would take the boy to a special centre for unaccompanied minors and that I did not know exactly how long it would be before she heard from officials. I wanted to make sure she knew he was fine.

I am accustomed to stories of hardship and fear but I have never gotten used to hearing these stories from children who undergo this traumatic journey, especially those who travel alone.

It was just one of those days. We provide psychological first aid to people crossing the border to make sure their basic needs are covered. Connecting with family members to let them know you are safe is one of the most impactful mental health interventions, especially during the critical moments after a traumatic event.

Day Two at End of the Wall camp

On another nontypical day, as I drive toward the End of the Wall camp, I encounter a group of 18 men from Nepal and Bangladesh who have walked about three miles west towards Sasabe along the hilly road next to the border wall. They crossed into the U.S. overnight and kept on walking, and now they are tired and had sat down to rest. The shoes of one of the men had no soles, so he had used his shoelaces to secure the insoles to his feet.

We give them water and snacks and ask them not to walk anymore, as the road is steep and there is little shade. The sun is about to come up for another hot day.

Further ahead, I come across another group of nine men from India walking along the road. We tell them to stop walking because it’s dangerous, and to wait for Border Patrol.

There are also more asylum seekers at the End of the Wall camp. There is a family from Chiapas, Mexico, who told us they fled cartel violence, leaving everything they owned behind. They feared their teenage daughter could be recruited into a prostitution ring.

I also meet a young mother from Guatemala and her three-year-old child. She said she used to own a corner store in the capital, Guatemala City, and was extorted by local gangs. “They told me that I would have to pay, or they would take my children,” she says.

A group of volunteers from Samaritans, drives out to check on people who left the camp on foot. Sally Meisenhelder is worried about those walking in the hilly road. “I have written messages in multiple languages on the tent telling people not to walk. They can be hit by a car,” she says. “When you come up over the hills [the driver] cannot see who is on the other side until they start to drop down. That is dangerous. Plus, they can’t make it all the way [to Sasabe].”

Several cars from Border Patrol arrive on schedule around 8 a.m. They ask people to line up and inform us that some of the asylum seekers have been picked up on the road. They ask unaccompanied minors, families and women to get in the cars first.

We say goodbye and wish them good luck, waving as they are driven away. After cleaning up, we drive for about 40 minutes to the place we are staying. When we arrive, we get a message from volunteers from Samaritans. More asylum seekers had arrived at the End of Wall camp after we left, and they stayed behind to help.

*Names changed to protect privacy.