In DRC, measles is spreading and killing again

Measles is once again on the rise in Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). The recent upsurge in cases – more than 13,000 since Jan. 1 – is a major source of concern for Doctors Withut Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF).

Between 2018 and 2020, the worst measles epidemic ever recorded in DRC tore through the country. In just two years, more than 460,000 children contracted the disease and nearly 8,000 died from it. Three-quarters of them were under five.

At the time, MSF had emergency teams in 22 of the 26 provinces, tracking virus hotpots, treating 90,000 patients and vaccinating more than 2.3 million children. Emergency responses were followed by supplementary vaccinations set up by the authorities for millions of children, which greatly reduced the number of patients, but did not cut the chain of transmission. Despite this, in August 2020, the Minister of Health declared the end of the epidemic.

A worrying increase

“Unfortunately, since the end of 2020, several provinces have started recording new increases in patients with measles, notably the North and South Ubangi provinces,” says Anthony Kergosien, MSF’s emergency response team coordinator in DRC. “We had to urgently send mobile response teams again to help stem the progression and save as many lives as possible.”

In December, MSF sent a team to the Bogose-Nubea health zone in South Ubangi. The needs they found there were massive. In only a few weeks, MSF treated nearly 5,000 patients with measles – the vast majority of them children. Teams vaccinated 70,000 children, halting the spread of the disease. The team then headed to the neighbouring province of North Ubangi, where the Bosobolo health zone was also in critical condition.

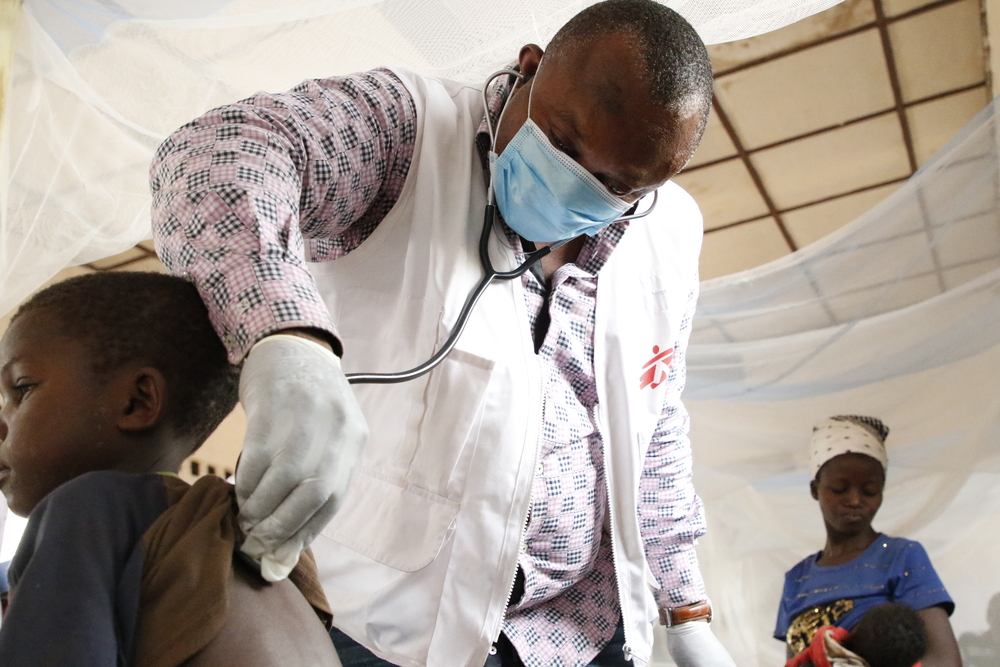

“Since we arrived in Bosobolo in mid-February, we have been helping staff to care for their patients in eight health centres and in the general hospital to which complicated cases are referred,” explains Faustin Igulu, who is leading the MSF project in Bosobolo. MSF has trained health centre staff how to manage patients with measles and supervises the provision of care, notably for patients with severe measles.

“More than 1,200 patients have already been treated,” he adds. “The hospital’s capacity had been quickly overwhelmed, so we increased the number of beds where they could treat children, some of whom were in a very advanced stage of measles and associated malnutrition.”

MSF also launched a vaccination campaign for 66,000 children in this isolated health zone and the work is ongoing, with a focus on those living in hard to reach areas. Teams also trained local health workers in disease surveillance to improve the early detection of new measles outbreaks. However, like many other health zones in DRC, the resources available to local health authorities fall far short of what is needed.

“The local health authority only has one motorbike, and it doesn’t work. How can they supervise vaccination activities?” continues Igulu. “How can they bring vaccines to the most remote areas? It’s very complicated.”

The most contagious disease in the world

Measles is a viral disease spread by coughing, sneezing or through direct contact with nasal or laryngeal secretions. Children with the disease can face severe complications, as measles ‘erases’ their immune memory, putting their health and lives at risk for years to come. An inexpensive and 85 per cent efficient vaccine exists, which protects vaccinated people for decades.

“Measles is the most contagious disease in the world, nearly 10 times more than COVID-19,” says Anthony Kergosien. “Winning the fight in DRC against this killer will require a vaccine coverage of 95 per cent with two doses per child, and regular mop-up campaigns to vaccinate those who slip through the cracks, including in the most vulnerable, difficult to access areas. But we are still very, very far from this.”

Enormous challenges

In Bosobolo, as in many areas of DRC, the fight against measles sometimes feels never-ending. Efforts to curb the spread of the disease face enormous challenges. A national vaccination and surveillance program has been hampered by major weaknesses; a very high birth rate exposes new children to the disease every day; an under-equipped health system is unable to ensure consistent quality healthcare; and health providers trying to access certain regions must overcome entrenched geographic and security difficulties.

Working to overcome these challenges is key to tackling measles in the long-term. Right now, we must not lose sight of the urgent need for an immediate response, which slows transmission and saves lives.

“MSF teams have been working in North Ubangi, South Ubangi, Bas-Uélé and Maniema provinces, but we sometimes feel quite alone in caring for patients and supporting local health teams,” says Kergosien. “Given the current increase in cases, it is imperative to increase the emergency response.”