COVID-19 in West Africa: ‘Let’s prepare for a long-distance run’

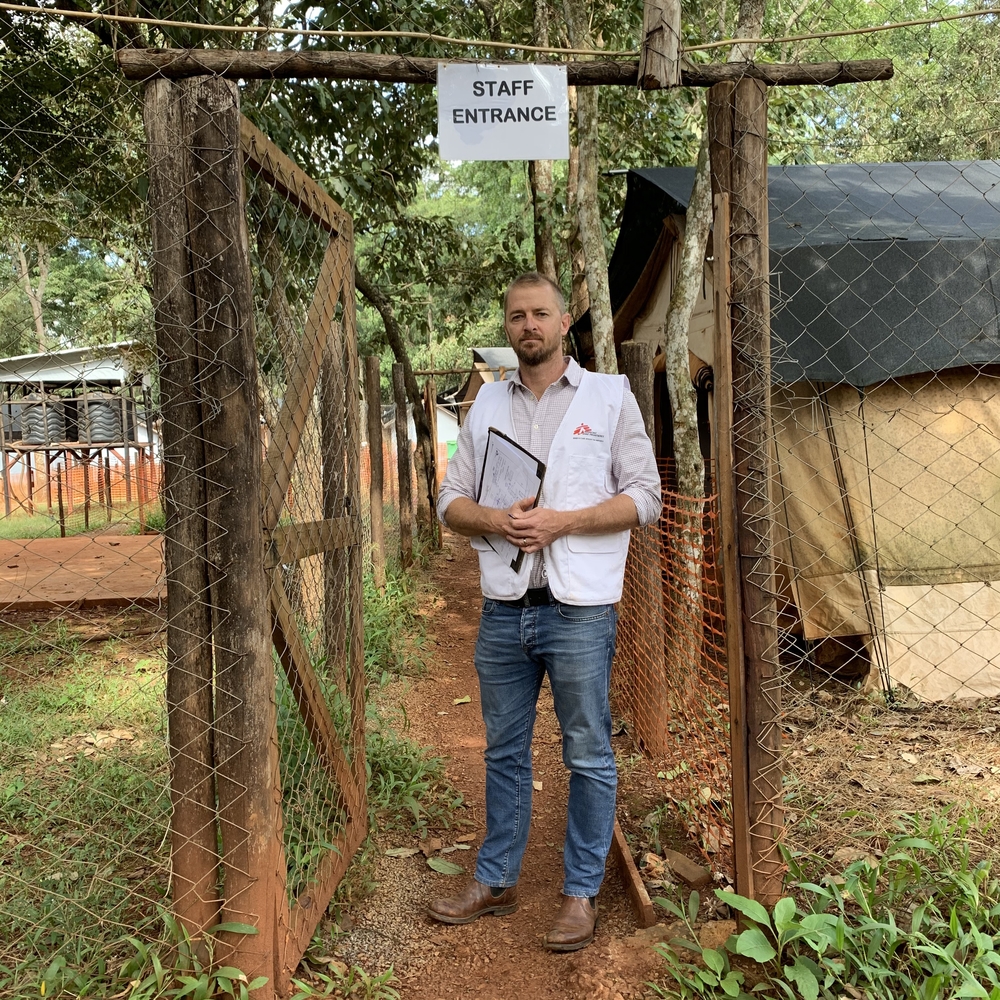

Doctor Chibuzo Okonta is President of Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) West Africa. Originally from Nigeria, he has been a volunteer for MSF since 2005. He has worked with the organization’s emergency medical teams in several countries of the region. Here, he calls on the practitioners from the African continent to own the narrative of the current pandemic and take advantage of the continent’s experience with outbreaks in order to propose a tailored response.

It has been close to three months now since the first case of COVID-19 was confirmed in Africa. The contamination curves are today much flatter than those seen in France, Italy or the United States. Contrary to what is happening elsewhere and in contrast to what was predicted for us, the epidemic has not exploded, health systems are not overwhelmed and mortality seems to be lower.

This is no reason to declare victory; but instead, a heads-up to prepare for a long-distance run.

To survive this marathon, doctors, researchers and all other stakeholders engaged in the response in the continent must take ownership of the narrative of the fight against the COVID-19 pandemic in Africa and provide evidence to rationalize and remove emotions from the on-going debate. Let’s not leave neither the panic, nor the fantasy of a protective exceptionalism of the continent to take over. We should instead prepare to offer cost-effective and efficient responses tailored to the local conditions.

Re-anchoring the debate in local communities

On March 18, Dr Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, WHO Director General, called on Africa to “wake up” to face the pandemic. A succession of alarmist speeches about Africa’s level of preparedness followed in international media. Yet, COVID-19 response in Africa cannot be reduced to a single territory; after all, Africa consists of 54 states, each at a very different level of preparedness.

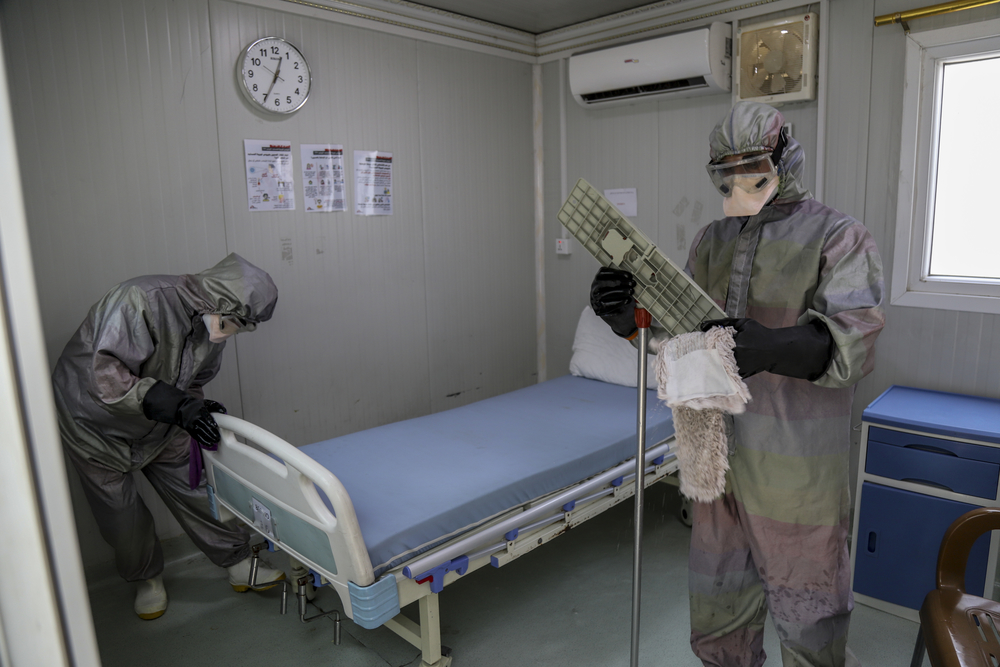

The new virus will undoubtedly claim casualties in our countries, but paradoxically, our health systems – usually said to be fragile – could be more resilient in addressing such shock. Most of our health workers did their medical studies and then practiced the art of healing in endemic and resource-deprived settings. They have learned and developed know-how, contrary to peers elsewhere. For example, basic preventive strategies, oft-repeated, are not new to our community. During an epidemic of Lassa fever (a regular occurrence in West Africa, recently in Sierra Leone or Nigeria), physical distancing and isolation rules were the same. We know from experience that the right information and protocols, enacted with people – rather than imposed on them, will break the contamination chains quicker.

Here is the thing: there is no monopoly of knowledge! Our healthcare systems certainly lack in the number of intensive care units and beds, as well as respirators. They certainly cannot claim sufficient numbers of qualified nursing staff to care for patients who will need oxygen. But we have developed resilience, skills and knowledge by means of managing emergencies and epidemics. We acknowledge our fragility, but this offers more opportunities for innovation. Our healthcare systems are aware of their limits and conscious about local capacities, but in the face of such an emergency, we are able to increase our capacity response and ready to perform a better triage. We learned from unfortunate experiences that we cannot save everyone.

Working with people

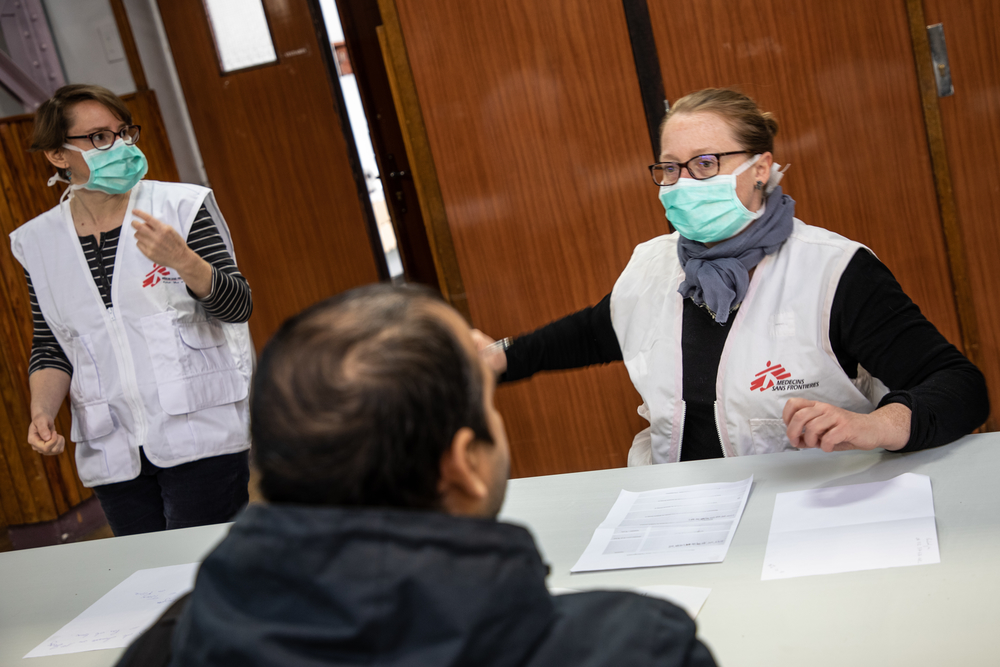

One thing to particularly keep in mind is the imperative to work with people. They have to be part of the debate and the action at every stage, be it prevention, preparedness or care. It is not just a question of designing and implementing a response, through self-protective habits, only made for a small middle and urban classes. Choices must be made in joint efforts.

The confinement issue should be tackled through this angle. The restriction measures put in place early on by our states enable us to slow down the spread of the pandemic and to better prepare. Yet, they will not prevent contamination, particularly in our densely populated neighbourhoods or family backyards. On top of that, they will have a very heavy economic and social impact on groups earning minimum daily subsistence.

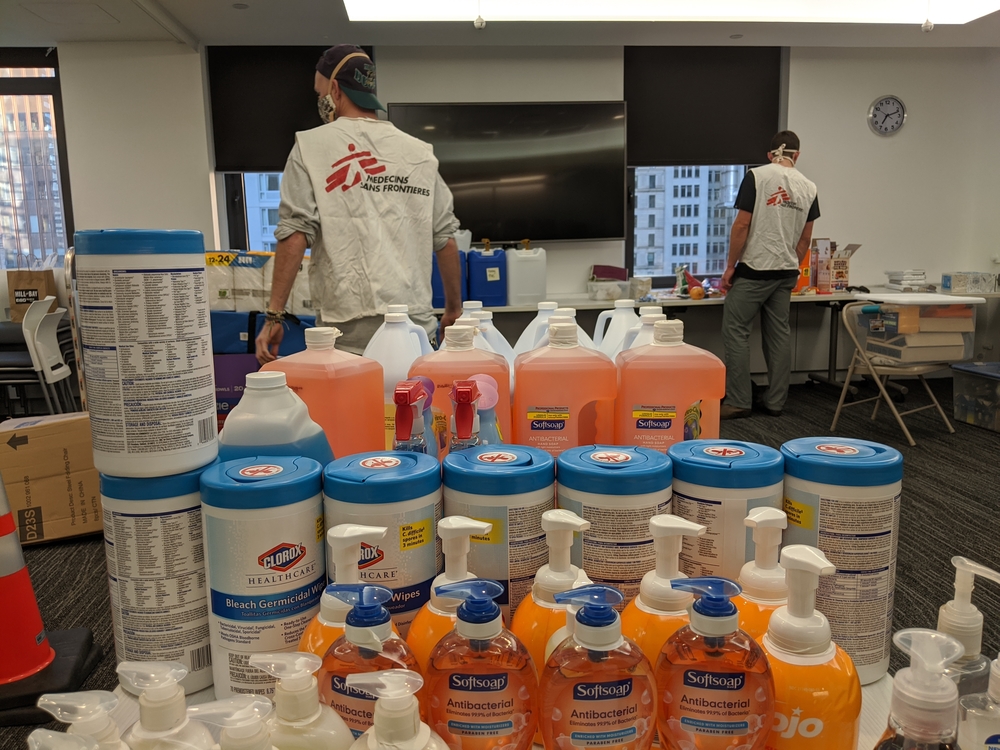

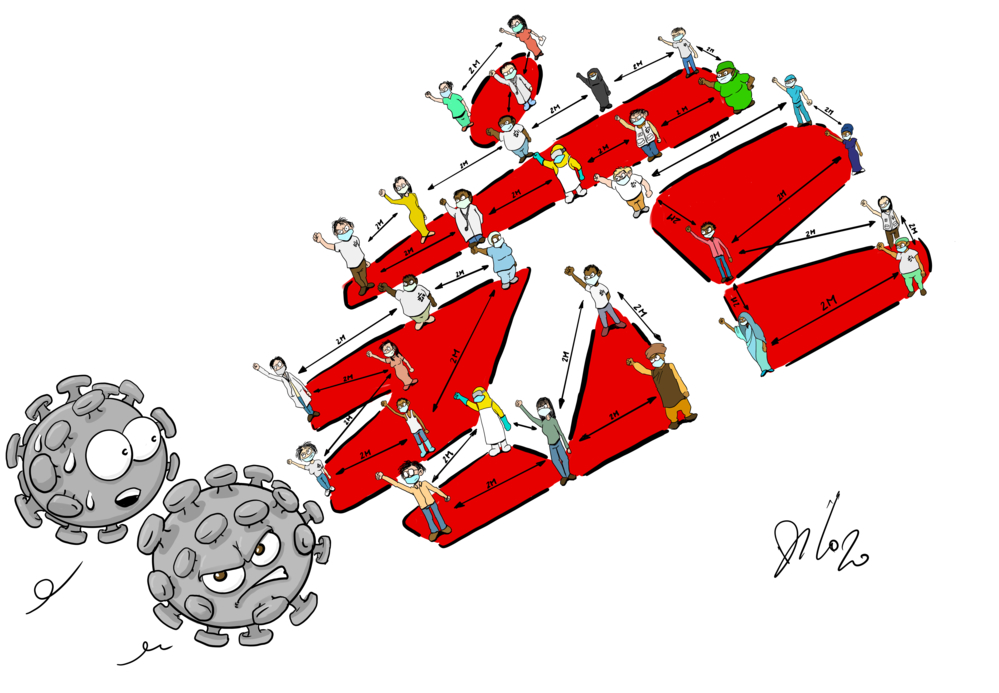

The collective approach has to be changed, in order to enable our fellow citizens to survive and to ensure that everyone reinforces the basic preventative measures: regular hand washing, good respiratory hygiene and respect for physical distance, as well as the wearing of masks. People must be assisted by making sure that the means are available and usable. In Côte d’Ivoire, for example, MSF teams have launched local manufacturing of cloth masks for distribution to the local people. “I protect you, you protect me”: we must also encourage local solidarity in response to the pandemic.

Informing and raising awareness is key to fighting an epidemic outbreak. It’s a right for populations and a duty for us, as medical doctors and researchers. The confidence with our fellow citizens has to be restored. This means that we have a duty of transparency about what we are doing, especially here, seeing the speed at which fake news circulates.

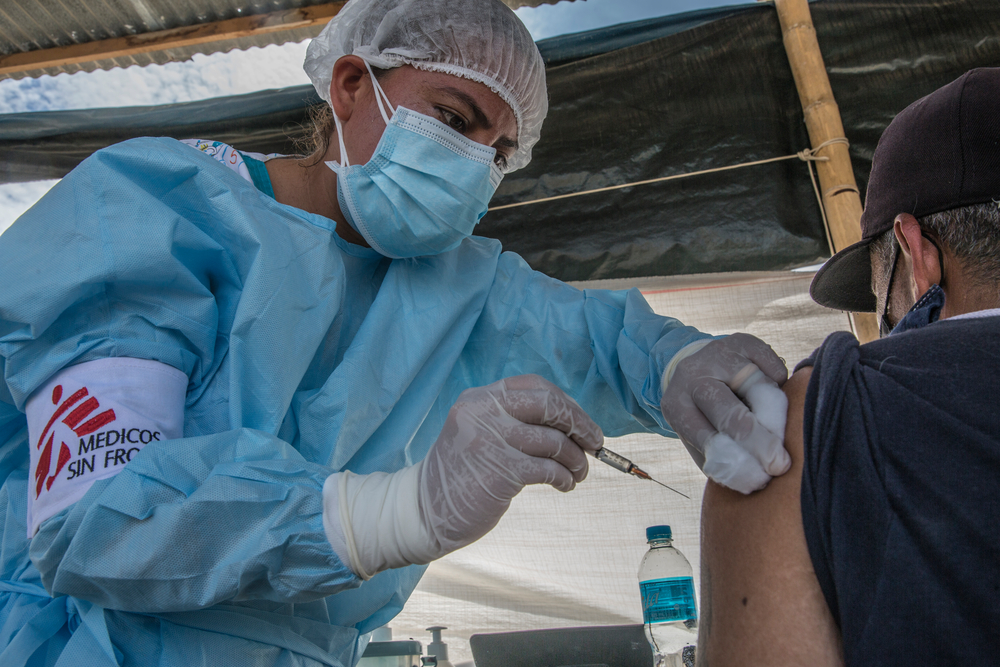

Yes, we do vaccinate populations in a preventive way. Yes, we do participate in clinical trials on treatments and vaccines. We did so before COVID-19, and we will keep on doing it afterwards – I hope – as this is a successful public health measure to protect populations from diseases such as measles, meningitis or Ebola.

For the record, the MenAfrivac vaccine, against meningitis A, was introduced in 2009, after several years of clinical trials. Mass vaccination campaigns have been achieved for 10 years and there has been no meningitis A outbreak in the region since then. Some of our readers might be too young to remember, but most of them have actually benefited.

Let’s speak directly with the population, to avoid any mistrust. Let’s encourage global solidarity, to address any turn down to the others or any discrimination, particularly when it comes to access to treatment and vaccines, should they become available. It is more than necessary to allow a large majority of people to reach the final line of this long-distance run.