Five things we can do to protect people on the move during COVID-19

The COVID-19 pandemic is disproportionately impacting the world’s most vulnerable. Among them are more than 70 million forcibly displaced people worldwide – refugees, asylum seekers, internally displaced people (IDPs), as well as migrant workers, including undocumented migrants.

Many of these men, women and children live in formal and informal camps, reception centres, or in detention centres. Others live on the streets in informal housing arrangements. Most lack access to basic services such as clean water, sanitation or inadequate access to healthcare, and many don’t have a legal status.

The COVID-19 pandemic both exacerbates and is exacerbated by these living conditions.

In these settings, preventative measures are often not possible. How can we ask people to protect themselves when they do not have easy access to water or soap? Or self-isolate when they live in cramped tents side by side with 10 other people? Physical distancing is very difficult, if not impossible, in overcrowded camps and dense urban settings, where people live side-by-side in small-congested shelters with many family members. Having to queue for water points and food increases the risks of contamination.

“In the [refugee] camp we live five or six to a container. I know that I can’t stop people coming in to see my room-mate and I have no choice but to gesture to people to keep away.”

– Frederik*, Refugee in Greece

“How can you ask people to stay at home to avoid infection? Where even is their home? We are talking about almost one million displaced people in Syria – at least one-third of Idlib’s total population – most of them living in tents in camps. They no longer have a home.”

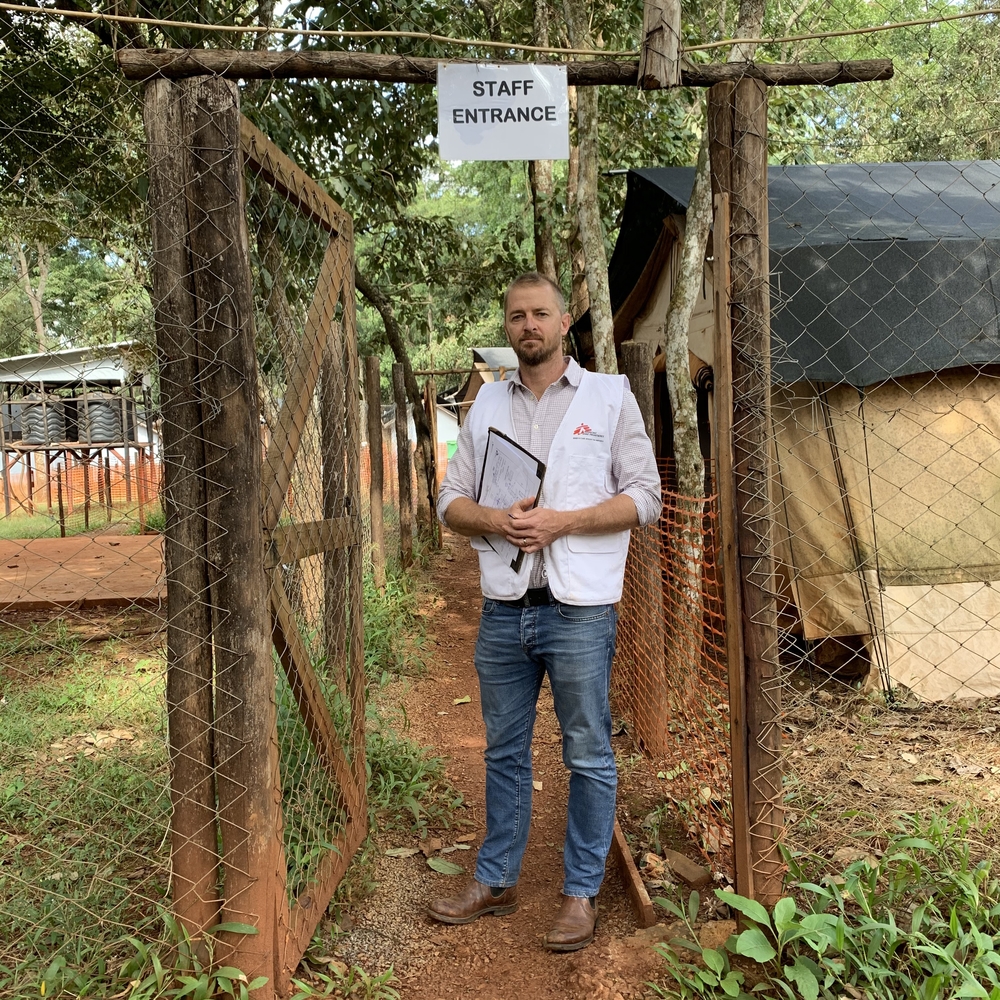

– Cristian Reynders, MSF Field Coordinator in northwest Syria

In many settings, displaced people live in insecurity, facing risk of arrest or abuse and may be stigmatised as ‘disease carriers’ against a backdrop of increased xenophobia, limited access to reliable information and are sometimes fully dependent on humanitarian aid. In many areas, such aid is limited.

Moreover, in many places the pandemic is being used as an excuse to punish people on the move, and those that seek to care for them. At least 167 states have fully or partially closed their borders to contain the spread of COVID-19 – 57 make no exception for people seeking asylum (UNHCR). People seeking safety and shelter are being turned away at land and on the sea – often returned or transferred to countries where they may face serious threats to their life or freedom. Together with border closure to limit the spread of the outbreak, many states are also purposely denying entry to asylum seekers or indirectly preventing their access.

“It was extremely hot, there was no food, and no water…[…] People drank salt water from the sea and died. We got one handful of dal and one capful of water per day. […] The men were beaten and became extremely malnourished, only skin and bone was remaining. We had to sit with our knees up to our chests for the whole time. Many people got swelling in their legs, became paralysed or died.”

– A fourteen-year-old girl, stranded on a boat for two months with 389 other people after Malaysia refused to rescue due to COVID-19 concerns

So what can we do to protect these especially vulnerable populations?

1. We must make sure that COVID-19 is not used as an excuse to enforce deadly migration control policies. Governments must not use COVID-19 as an excuse to enforce further restrictive migration control policies and evade international obligations towards refugees, asylum seekers and migrants. We understand the serious challenges presented by COVID-19, but safeguarding the wellbeing of those in your own country and upholding your international obligations towards refugees, asylum seekers and migrants are not mutually exclusive principles.

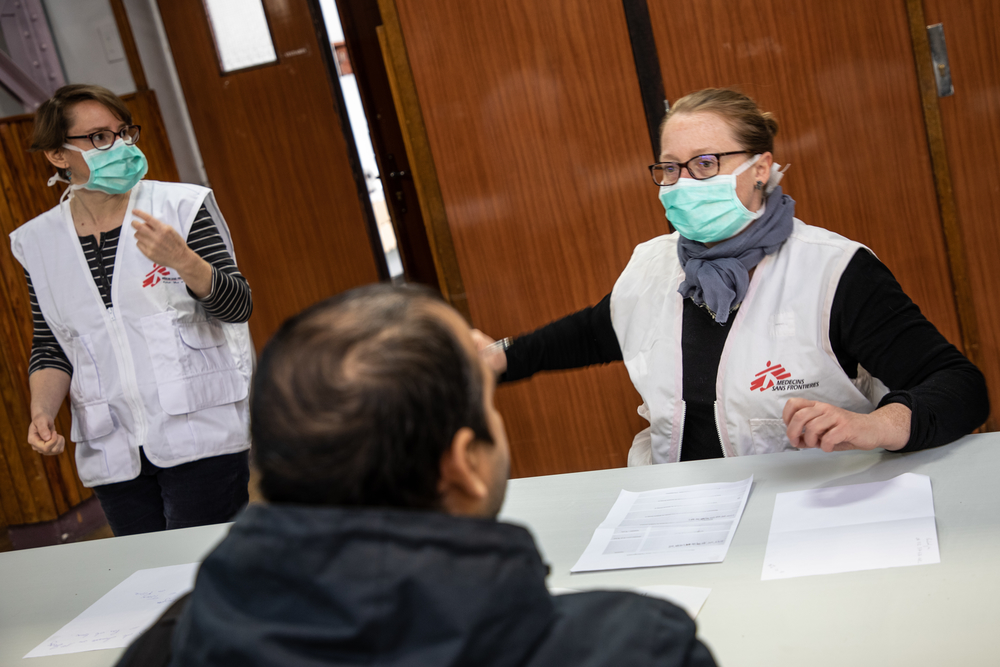

2. We need to ensure human rights are respected. Governments must not use COVID-19 emergency public health measures to target refugees, asylum seekers and migrants. All restrictions on rights must be strictly necessary, based on scientific evidence and not applied arbitrarily or discriminatorily. They must be limited in duration, respectful of human dignity, subject to review, and proportionate. Governments must also continue to allow people to follow legal processes to request asylum.

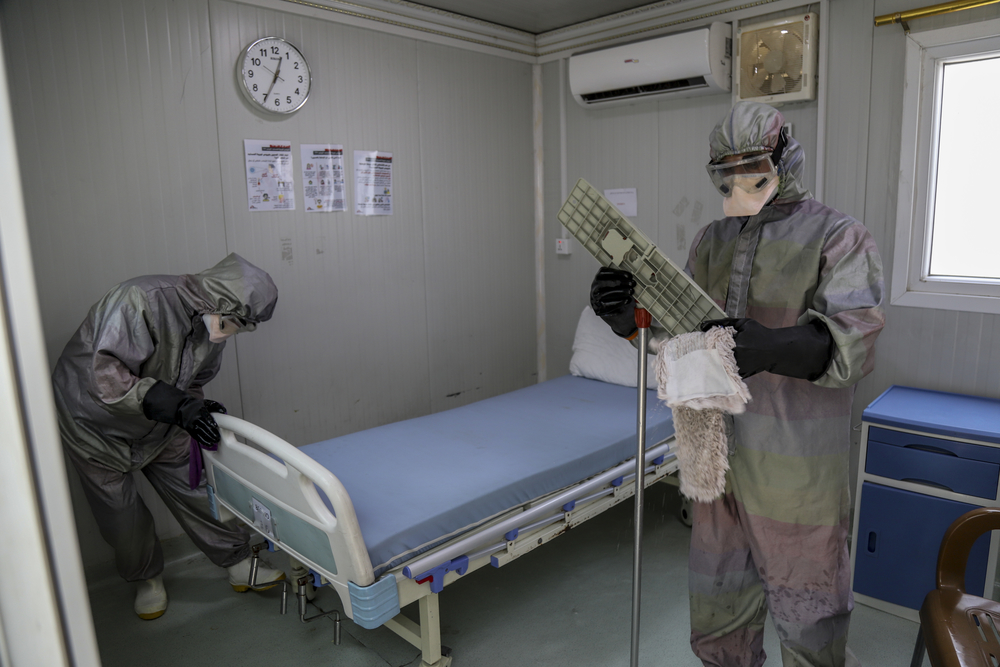

3. Lockdowns and mass quarantining cannot be cut-and-pasted or discriminatorily applied. Quarantine and lockdown measures should be applied equally to all without discrimination; healthcare, social and psychosocial support, and basic needs as food, water and other essentials should be provided to those in quarantine; and mass quarantine should be avoided where possible. Forcing people to live in overcrowded and unhygienic camps was always irresponsible but now more than ever due to the COVID-19 threat.

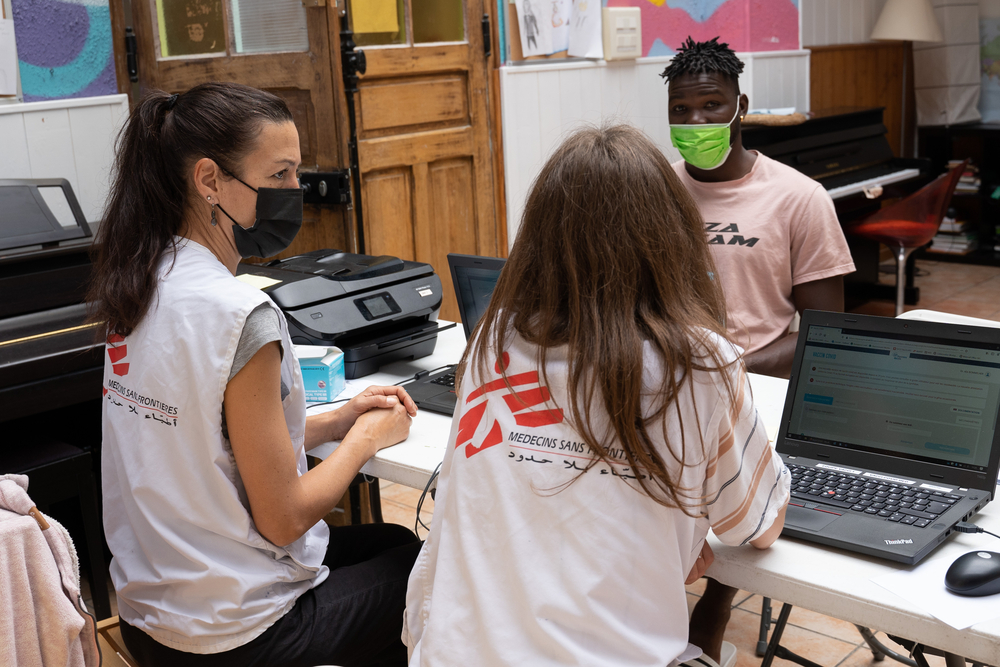

4. Displaced people at risk should be evacuated whenever possible. Where possible, MSF is calling for the evacuation of vulnerable refugees, asylum seekers and migrants. In Greece on the island hotspots MSF is calling for the evacuation of people the most at risk (people above 60 years and those with respiratory conditions, diabetes, or other health complications) as well continuing efforts to decongest the camps, including relocating unaccompanied minors and sick children to other EU member states. In Libya MSF is calling for the international community and the European governments to put in place direct humanitarian evacuation corridors for the most vulnerable refugees, migrants and asylum seekers exposed to the most imminent life-threatening risks, including those trapped in detention centres across across the country and in other places of captivity.

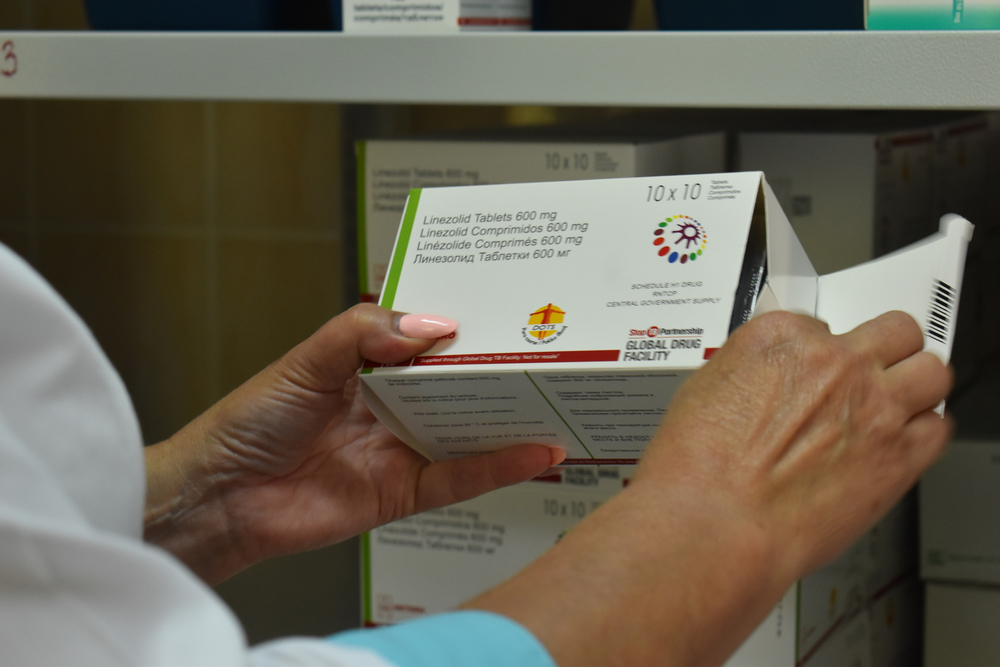

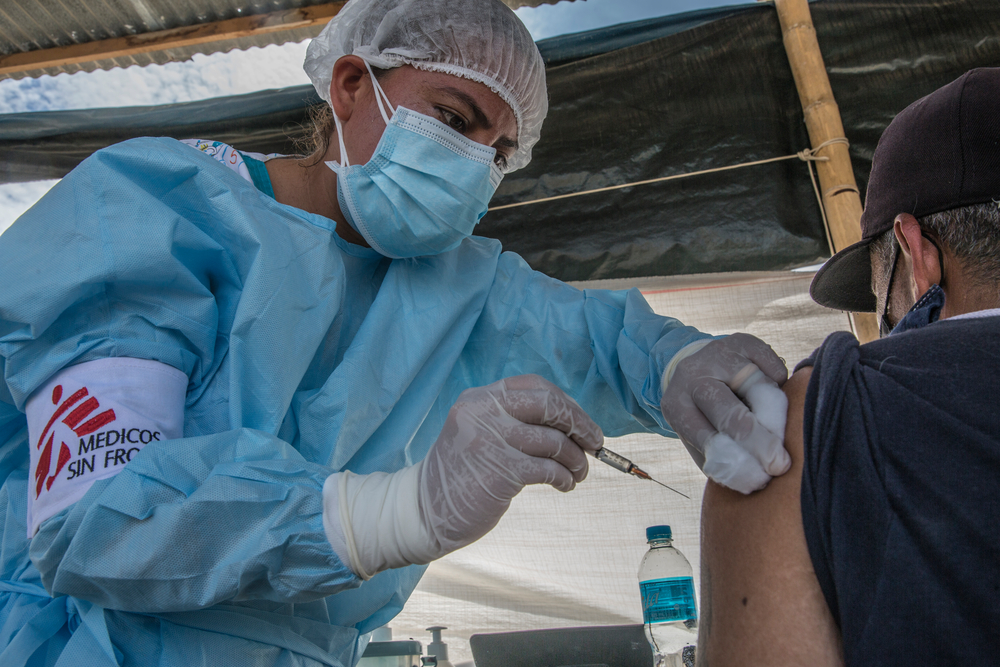

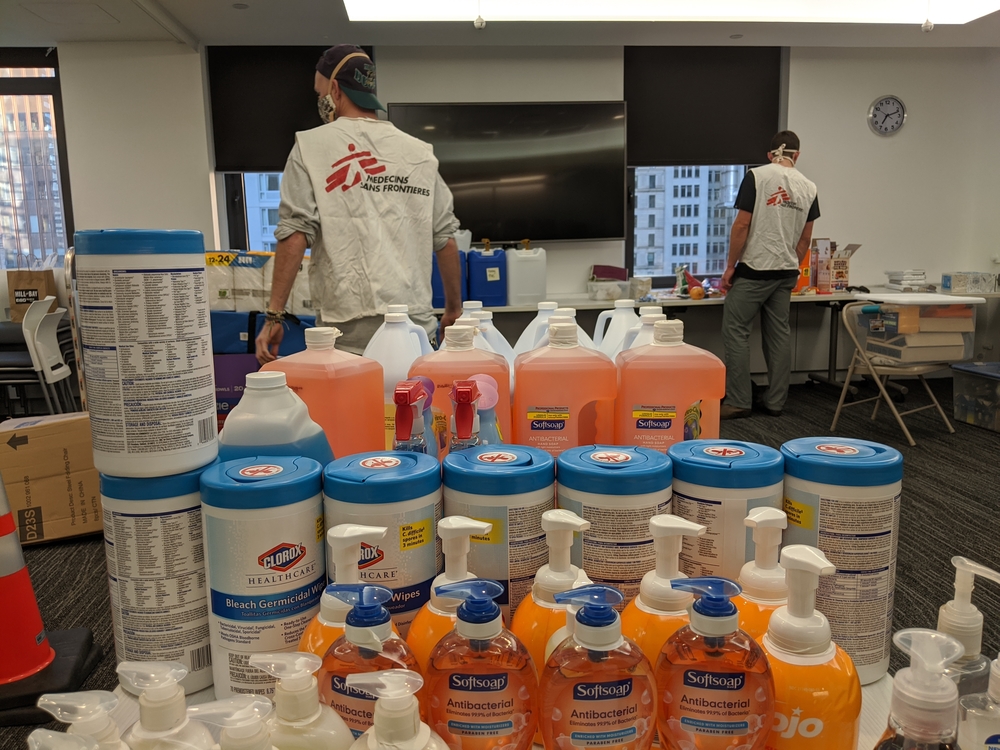

5. We need to safeguard the access to healthcare for all. COVID-19 control measures should not come at the cost of access to urgently needed healthcare. This means border closures must not stop urgently needed medical and humanitarian supplies, as well as medical and humanitarian staff, from coming into countries. Furthermore, governments must ensure restrictions in camp, detention or reception settings do not block people from accessing healthcare.