Tanzania: 5 ways MSF is supporting malaria prevention

In Kigoma region, in north-western Tanzania, Doctors Without Borders/Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) has been providing health care to Burundian refugees living in Nduta camp, as well as Tanzanians in neighbouring host communities for over eight years. During the rainy season, malaria is highly endemic, leaving its residents vulnerable to contracting malaria year-round. The risk of exposure to malaria is especially high in February, March and April, due to the rainy season, when stagnant water and puddles offer the mosquitos ample breeding ground.

Beyond monitoring and responding to peaks of malaria in our emergency department, since 2017 our MSF teams also conduct preventative medical and water and sanitation activities, to reduce and control malaria vectors in Nduta camp and in nearby villages, such as Kumhasha, Biturana, Maloregwa and Nengo.

Here are 5 ways MSF teams are supporting malaria prevention:

1. Mosquito traps

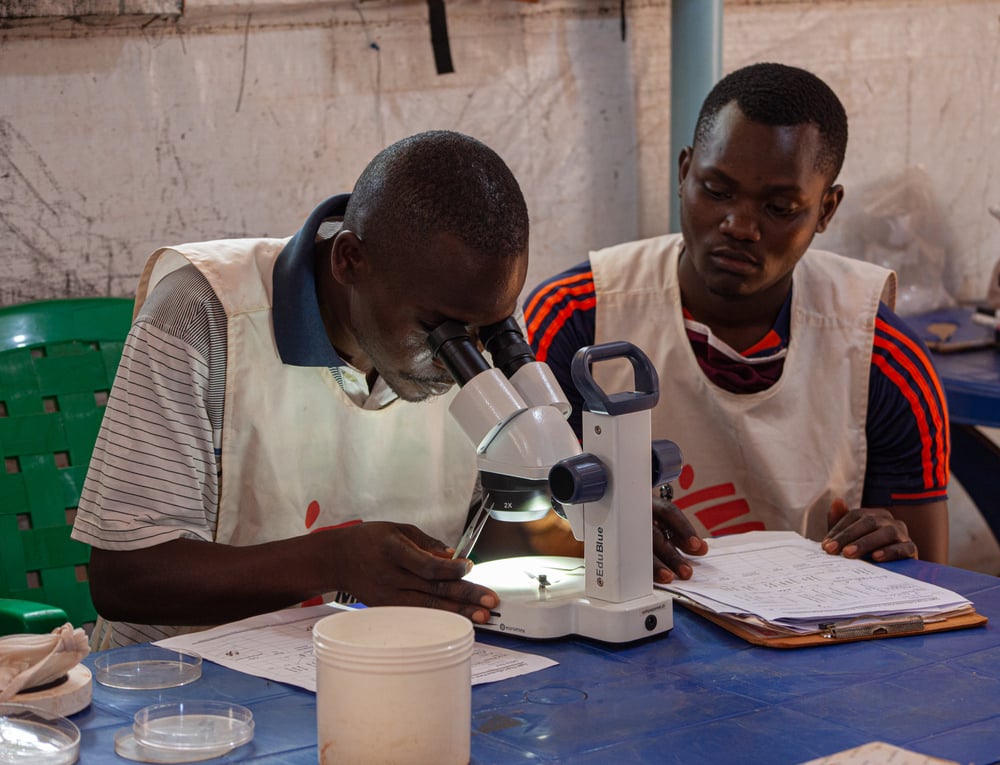

Mosquito traps attract and catch host seeking mosquitoes, to monitor the number of malaria transmitting mosquitoes and to support analysis on how many mosquitos are carrying malaria. This also reduces the number of mosquitoes in the room. With this analysis mosquito maps can be made to track which areas have the highest incidence of infected mosquitoes and determine how best to reduce the spread of the disease. Our teams monitor incidence of mosquitoes by zones in the camp, to see which zones have the highest incidence, and how to intervene. Analysis on how many mosquitoes are carrying malaria is done once per year.

2. Data collection, analysis and mapping

Our teams conduct surveys to identify high incidence areas and to inform prevention activities. MSF monitors data from the Tanzanian Red Cross Society’s outpatient department, which provides data on incidence of malaria by zones.

Using maps created by Geospatial Information System (GIS) specialists, MSF teams determine how best to reduce the spread of the disease based on analysis collected from the mosquito traps, as well as medical data from the clinics to track the number of cases by zone within the camp.

3. Larviciding

During the rainy season, the heavy rainfall in the region increases the incidence of stagnant water, large puddles and swamps, which provides a perfect breeding ground for the mosquitoes to multiply and spread the disease. In response, MSF teams carry out larviciding, which involves spraying a non-toxic chemical called Bactivec to kill mosquito larvae in swamps and stagnant water in and around the camp and neighbouring villages. By killing the mosquitos at the larvae stage, they are still too young to disperse and infect anyone with the disease.

4. Indoor residual spraying

Indoor Residual Spraying (IRS) consists of spraying insecticide inside buildings or structures to prevent mosquitos from coming in. MSF sprays the hospital structures twice a year to keep our patients safe from malaria.

5. Mosquito nets

Mosquito nets are set up in the house around the bed, to protect people from mosquito bites while they sleep. While MSF has handed over most of the mosquito net distribution activities to local partners, it still gave out 318 mosquito nets to sickle cell patients in 2022, at the start of rainy season.

MSF continues its work to prevent and treat malaria while calling for more effective and sustainable solutions to fight the disease, and to reduce the number of cases and preventable deaths.

MSF in Tanzania

MSF has been working intermittently in Tanzania since 1993, responding to different needs and emergencies countrywide, including malaria, HIV/AIDS, cholera, water provision, primary and secondary health, emergency preparedness for disease outbreaks, refugee health needs, and other health programmes to improve people’s access to healthcare.